The New York Times Protests Too Much

It’s been a heck of a month for hating on the New York Times.

I won’t claim to be the elder statesman of Being-Mad-At-The-New-York-Times among professional Democrats, but I am certainly an elder statesman in this matter. I grew up loving the Times — growing up in a town of 300 people I literally saved up so that I could occasionally buy the Sunday edition of the New York Times when I happened to be in Ithaca on the weekend. Then I gained regular access to it, and my perception of the paper shifted dramatically: The paper’s obsessive, often wrong, and nearly-always misleading coverage of Whitewater, its cozy relationship with the sinister Ken Starr, its evident institutional crush on George W. Bush and even more evident contempt for Al Gore, its central role in helping Bush lie his way into war in Iraq — all of this and more added up to something very obvious that I was amazed more people working in Democratic politics couldn’t see. So while Media Matters for America has generally been best known for its essential work taking on the likes of Fox News and Rush Limbaugh, the news company that most motivated my work in helping create and lead the organization twenty years ago was the New York Times.1

Naturally, I read the recent Politico article about a simmering feud between the Biden House and the New York Times with great interest. And Times executive editor Joe Kahn’s interview with Semafor’s Ben Smith with great exasperation. I haven’t written about either because, frankly, I don’t have anything to say about the New York Times that I haven’t said a thousand times before over the last 25 years – and because over the last month plenty of others have been eager to take up the cause. That isn’t always the case, and although I’m more than happy to live with the downsides of being a persistent critic of the world’s most influential news company, I don’t mind taking the occasional break from repeating myself.

The thing is, though: I believe what I wrote a few months ago: Yes, Democrats should criticize the New York Times. So at risk of repeating myself …

The model of journalism the New York Times pretends to believe in is bad – and the Times knows it

A striking thing about this dust-up is that the partisans are delivering clear, principled statements about what journalism should be, and the journalists are responding like campaign hacks — inventing straw men to debate and offering an endless stream of vague platitudes.

That’s not particularly new, though: You can spend a lot of time scrutinizing the public comments of the leadership of The New York Times2 and never find a clear, unambiguous explanation of how the paper thinks it should cover fundamentally unequal or dissimilar things like, say, Donald Trump and Joe Biden. But if you read between the lines a little bit, paying particular attention to what the paper says it shouldn’t do,3 and combine that with what we can infer from the Times’ coverage, a pretty clear picture emerges: The Times thinks — or wants people to think it thinks — that independent, “balanced” journalism means generating a roughly equal volume of positive and negative coverage of the two candidates.

The current dust-up between the Times and progressive critics kicked off with that that POLITICO piece, so let’s start there. Here’s how POLITICO described the Biden White House’s view of the Times:

“[T]hey see the Times falling short in a make-or-break moment for American democracy, stubbornly refusing to adjust its coverage as it strives for the appearance of impartial neutrality, often blurring the asymmetries between former President Donald Trump and Biden when it comes to their perceived flaws and vastly different commitments to democratic principles.”

I’ll pause here and say that I’m absolutely delighted to see such a critique of the New York Times coming from a Democratic White House. Note that the White House critique is both clear and principled. They aren’t arguing for journalists to be partisans, they’re advancing a vision of journalism — one that makes asymmetries clear rather than blurring them — that is at a very minimum utterly defensible.

Last week, in an interview with Semafor’s Ben Smith,4 Times executive editor Joe Kahn responded to that POLITICO article and to a recent newsletter by Dan Pfeiffer:

“[T]he role of the news media in that environment is not to skew your coverage towards one candidate or the other, but just to provide very good, hard-hitting, well-rounded coverage of both candidates, and informing voters. […] To say that the threats of democracy are so great that the media is going to abandon its central role as a source of impartial information to help people vote — that’s essentially saying that the news media should become a propaganda arm for a single candidate, because we prefer that candidate’s agenda. […] I don’t even know how it’s supposed to work in the view of Dan Pfeiffer or the White House. We become an instrument of the Biden campaign? We turn ourselves into Xinhua News Agency or Pravda and put out a stream of stuff that’s very, very favorable to them and only write negative stories about the other side?”

Kahn’s response to criticism is extremely disingenuous. Nobody is saying the Times should be an instrument of the Biden campaign, or run only positive stories about Biden and only negative stories about Trump.5 Kahn’s response is the kind of evasive and disingenuous spin and ridicule you would expect from a campaign hack.

Kahn’s answer is also extremely revealing. The criticism of the Times is that it blurs the asymmetries between Trump and Biden. Kahn rejects and ridicules this, suggesting that to produce journalism that treats asymmetries as asymmetric would be to become “an instrument” of one campaign, akin to Pravda. The implication of this exchange is clear: The Times thinks its negative coverage of the two candidates should be of equivalent volume, and the same for its positive coverage. To do otherwise, according to Kahn, would be to become a tool of one campaign — a “propaganda arm.”

The same implication was present in Times’ publisher AG Sulzberger’s comments the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism earlier this year:

“We are going to continue to report fully and fairly, not just on Donald Trump but also on President Joe Biden. He is a historically unpopular incumbent and the oldest man to ever hold this office. We’ve reported on both of those realities extensively, and the White House has been extremely upset about it. We are not saying that this is the same as Trump’s five court cases or that they are even. They are different. But they are both true, and the public needs to know both those things. And if you are hyping up one side or downplaying the other, no side has a reason to trust you in the long run.”

Even as Sulzberger acknowledges that Joe Biden being four percent older than Donald Trump and Donald Trump being a criminal are of course not equivalent things, the overall implication of this passage is that the Times does in fact treat them as equivalent; that it thinks the amount of positive (“hype”) and negative (“downplaying”) coverage it gives each candidate should be roughly equal.

This implication appears over and over again in the public comments from Times leadership. A year ago, Sulzberger wrote a lengthy piece in Columbia Journalism Review rejecting many common critiques of the Times, refuting the criticism that “journalists … treat unequal things equally” and claiming “the both-sidesism argument … has the feel of media critics fighting the last war … they attempt to win a debate by avoiding one6 … these efforts attempt to reduce wide-ranging lines of coverage into a single statement about what is most true and important, rather than to reflect the reality that many things can be true and important at the same time.” In 2022, Kahn similarly told Vanity Fair: “The idea that the Times is stuck in some 1980s paradigm of both-sides journalism, where we don’t help readers sort out what’s really true or untrue, is pretty factually false. […] I don’t think though that that’s the same thing as saying that we are devoted, as an institution, to ensuring that one side or the other in a two-party political system is best positioned to win elections. That’s a partisan motive. […] We need to hold ourselves to account for reporting in a well-rounded way on all the big controversies of the moment.”

Again and again the leaders of the New York Times leaders respond to the criticism that they treat unequal and asymmetrical things equally and symmetrically by saying the alternative is to be “partisan” and an “arm” of a political campaign. It isn’t, but by responding this way the Times in effect concedes the accuracy of the criticism.

Notice that they never quite say directly what they are obviously implying. I think the people who run the New York Times understand that the version of “balance” that they are advocating (which is not actually balanced at all — more on that later) seems fair and reasonable if you catch it out of the corner of your eye, but if you take a good look at it head-on, the absurdity is obvious. So they hint at and gesture towards a belief that “balanced” coverage means giving both candidates the same number of positive and negative articles – but they won’t actually say that explicitly.

The Times declares its independence while tilting its coverage to favor the Right

At some point in recent years Times leadership abandoned the word “balance” and adopted “independent” as its mantra, likely because the critique of false balance has become so widely accepted. In his Semafor interview, Kahn used the word “independent” three times to describe the Times’ approach to journalism. It was the core theme of Sulzberger’s lengthy 2023 Columbia Journalism Review piece, summarized in the Times’ flagship newsletter as “The Case for Journalistic Independence.”

So what does “independence” mean? That the paper won’t take orders from anyone outside the building? Sure. Nobody is suggesting it should. That isn’t a useful definition.

I submit that the meaningful version of independence is simple: The news media should tell its audience true things, in proportion to their importance, with no concern for how anyone feels about it.

The New York Times, by its own admission, does not do this. The Times doesn’t even try to do this. The Times instead tries to “balance” its coverage in order to appeal to a segment of the country that, according to the New York Times, is not even its audience. It shapes its coverage — abandoning proportionality — in an attempt to earn the trust of people who do not read it and will never trust it. This is the opposite of independence.

Take another look at Sulzberger’s defense of the Times covering Joe Biden’s age with the same gusto it devotes to Donald Trump’s criminal trials: “if you are hyping up one side or downplaying the other, no side has a reason to trust you in the long run.” So a desire to win the trust of Trump supporters motivates the Times’ editorial decisions. Similarly, in a 2022 joint interview with his outgoing predecessor, Dean Baquet, Kahn told CJR “I’m definitely interested in continuing to increase the readership and the reach of the New York Times, including among people who do not identify as Democrats.” That led Baquet to elaborate: “Look, I think we have to have a broad audience. I don’t think it’s healthy. I mean, it was a century ago that news organizations started to try to have broad audiences, that the days of a left-leaning paper and a right-leaning paper sort of went away. I think it’s unhealthy, honestly, to have an audience that’s not as broad and as rich as possible. I think it’s not healthy for the institution. If you believe that you’re supposed to listen to your readers and try to serve your readers, if you only have one kind of reader, I just don’t think that’s healthy for us. But more importantly, I don’t think it’s healthy for the society.” After Kahn’s interview with Semafor, star Times reporter Peter Baker told Fox News “Joe’s got it just right … A free press serves democracy by being independent, not by joining a team. […] to the extent that people think that we’re on one partisan side or the other, it undermines the authority of our reporting.”

Again and again and again, the New York Times tells us that winning the trust of Republican (non-)readers is a key motivator in the paper’s approach to journalism. Criticized for treating unequal things as equal, for blurring asymmetries between candidates, the Times insists that to do otherwise would cause the paper to lose the trust of Republicans, who already do not trust the Times and never will, which means the Times just keeps lurching rightward to appeal to people who keep moving further and further away from it.

In short: The Times defends itself from criticism for presenting a distorted view of the choice between Biden and Trump that blurs the asymmetries between the candidates by insisting that it must do so in order to appeal to Trump supporters.

This is simply not what “independence” means.

On some level, I think AG Sulzberger knows that. In his Columbia Journalism Review piece, Sulzberger wrote reverentially of his “great-great-grandfather, the founder of the modern New York Times,” who “entrusted his successors ‘to maintain the editorial independence and the integrity of the New York Times and to continue it as an independent newspaper, entirely fearless, free of ulterior influence and unselfishly devoted to the public welfare.’”

But you are not “an independent newspaper, entirely fearless, free of ulterior influence” if your editorial decisions to treat asymmetrical things as symmetrical is motivated by a desire to appeal to one political faction, as Sulzberger and his top leadership repeatedly indicate is the case. That makes a mockery of Adolph Ochs’ insistence on journalism “without fear or favor.”7

The basic journalism concepts journalists get wrong

I’ll conclude by stepping back a bit from the current debate The New York Times is losing with nearly every thoughtful observer.

There’s a fundamental confusion at the heart of the broken way most political journalists — definitely not just at the New York Times — have approached their jobs for decades. A confusion about what the various buzzwords they have deployed over the years to describe their approach actually mean. “Balance,” “Independence,” “Fairness,” “Objectivity,” “Neutrality” — these are (related and overlapping) values we constantly see journalists tout. They are all great values that should be at the heart of journalism.

I just don’t think they mean what many political journalists think they mean. These values are typically invoked by journalists to defend coverage that treats asymmetrical things as symmetrical, and inequivalent things as equivalent.

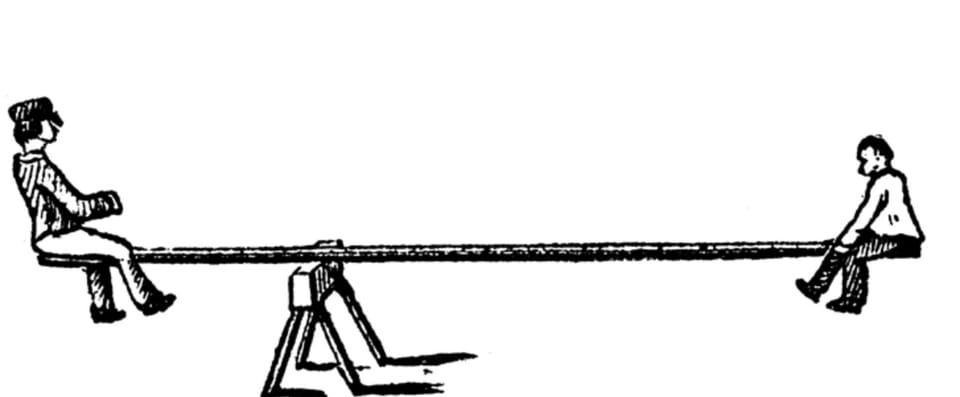

Picture a seesaw with two people of very different sizes, and the fulcrum moved toward the heavier person:

These two people are “balanced” on the fulcrum. But in order to achieve this balance, the fulcrum is placed to favor one person. The people may appear at a glance to have equal weight, but this is misleading — because the seesaw itself is not balanced, as we would quickly see if there were no people on it.

To me, “balanced” journalism doesn’t mean coverage that makes the candidates look equal, it means coverage that applies the same standards to both candidates. If one candidate tells 20 lies and the other candidate tells 2,000 lies and a news organization runs six articles about each of them being dishonest, that isn’t “balanced” journalism — it’s journalism that favors the candidate who lies more often, in order to make the candidates appear to be in balance.8

“Balanced” “objective” “neutral” “impartial” journalism doesn’t mean giving the reader an equal amount of good and bad information about each candidate. It means applying the same standards to each candidate. It’s about applying an equitable process, not ensuring equal outcomes.

So I come back to this: The news media should tell its audience true things, in proportion to their importance, with no concern for how anyone feels about it.

That’s what democracy requires of journalists. And that’s what it means to practice independent journalism, “without fear or favor.”

I have had no affiliation with Media Matters for about a dozen years. I remain deeply proud of my work in the organization’s early years and of the work it has gone on to do without me. ↩

I have. ↩

Which is generally a straw man caricature of what the Times claims its critics want. ↩

Smith previously worked at the New York Times, and tossed Kahn a steady stream of softballs, making it all the more remarkable that Kahn’s responses were so bad. ↩

As CNN’s Oliver Darcy noted: “Kahn's answer feels overtly disingenuous. It is, of course, entirely feasible to express concerns about Trump's anti-democratic rhetoric and acknowledge them in a real way without morphing into a ‘propaganda arm’ for President Joe Biden. In fact, I am not aware of anyone who has called for The NYT to treat Biden like Fox News treats Trump.” And Pfeiffer, in a more-gracious-than-I-would-have-been response to Kahn’s caricature of his critique, added: “In general — and this is a complaint I have had about the New York Times that is two decades old — I wish they would take good faith criticism from the Left with as much seriousness as they take bad faith criticism from the Right.” Yep! ↩

Yes he really said that. ↩

This originally incorrectly referred to “Arthur Ochs” Ochs rather than “Adolph Ochs.” Arthur Ochs Sulzberger was Adolph Ochs’ grandson and, like his grandfather, his father Arthur Hayes Sulzberger, his son Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr., and his grandson Arthur Gregg Sulzberger, served as publisher of The New York Times for purely meritocratic reasons, I am sure. In any case, it was Adolph Ochs laid out the “without fear or favor” construct his descendants Arthurs have been making a mockery of ever since. I regret the error. ↩

This is not a new critique; I’ve been making it for at least a quarter century, along with many others. Nor was it new then. There’s a scene in perhaps the most famous campaign documentary film ever made, 1993’s The War Room, in which James Carville — perhaps the most famous political strategist of the past half century — ridicules the news media: “If we say ‘fifty plus fifty is a hundred and four’ and they [Republicans] say ‘fifty plus fifty is a hundred-and-four-thousand,’ [the news media will] say ‘well both of them are stretching the numbers a little bit.’” ↩

Member discussion